Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2022.

The recent increase in energy prices constitutes a significant supply shock, which could therefore also have an impact on the potential output of the euro area economy. Based on the assumptions used in the June 2022 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, oil prices in US dollars in the period 2022 to 2024 are expected to be around 40% higher than their levels in the pre-COVID period (2017-19).[1] Expressed as a percentage, the increase in oil prices since 2019 is smaller than the 1973 and 1979 shocks (Chart A).[2] In addition, the increase observed between 2003 and 2008 turned out to be of a greater magnitude than the current increase. The nature of the current oil price increase – largely a supply shock linked to supply bottlenecks and to the war in Ukraine – is more comparable to the 1970s shocks than to those of the 2000s, when demand for oil played a major role in the rise in fossil fuel prices.[3] Since the current increase in energy prices, and oil prices in particular, reflects supply-side factors, it could also affect potential output and the output gap, with implications for inflationary pressures. This box describes the channels of impact and uses elasticities estimated on historical data to shed light on the risks to potential output stemming from the current increase in energy prices.

Chart A

Annual relative change in crude oil prices in US dollars

(index = 1 in the year preceding the shock)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: This chart shows the relative change in the oil price, expressed in US dollars, for the five years before and after each exogenous shock, where t0 stands for the year preceding the surge in oil prices. For the 2020 shock, the oil price is based on the June 2022 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, which are based on oil futures prices on 17 May 2022.

With regard to the channels of impact, economic theory suggests that under certain conditions permanent oil price changes can be negatively correlated with each of the determinants of potential output.[4] The capital stock is mainly affected by two opposing effects. First, the oil price itself as an input in the production process can be seen as a component of the user cost of capital and may affect investment decisions. Second, the price of oil is negatively correlated with the degree of utilisation of the capital stock and thus with the depreciation rate. Overall, in both cases, if the elasticity of substitution between oil and the other intermediate inputs is greater than one, there is a negative relation between oil prices and the existing capital stock, and therefore potential output. An increase in the oil price reduces total factor productivity, since higher oil prices lead to obsolescence of oil-intensive production technology and thus a decrease in the value added from production. In addition, increased transportation costs resulting from higher oil prices could lead to a decrease in the incentive to specialise and therefore a drop in productivity growth. The impact of higher energy prices on labour market trends depends on the extent to which workers’ wage demands adjust to the increase. A rise in the price of energy initially raises costs and reduces companies’ profits if nominal wages do not adjust. Restoring employment and profitability to their initial levels requires some combination of lower nominal wages and higher output prices. Either way, real wages and the unemployment rate that does not generate wage or inflationary pressures (called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment or NAIRU) may be negatively affected and permanently alter labour supply.

However, there is no clear empirical evidence that oil price shocks have a lasting effect on potential output. While Fuentes and Moder (2020) suggest that the 1973-74 oil embargo imposed by OPEC only had a negative effect on global potential output in the first year after the shock, which was swiftly reversed in the following years, some studies have found small effects on long-term real GDP growth.[5] Blanchard and Galí (2008) find for a set of OECD countries that oil price shocks have lost significance as a source of economic fluctuations from the 1970s until today.[6] They claim that this stems from more flexible labour markets, improved monetary policy and the fact that those economies have a lower oil intensity compared with the 1970s. When the first oil price shock hit the global economy in 1973, approximately one barrel of oil was required to generate USD 1,000 of GDP in 2010 prices. Today less than half that amount of oil is needed to generate the same level of output.[7] For euro area economies, this drop has probably been even larger (Chart B) since their energy mix is much less dependent on fossil fuels.

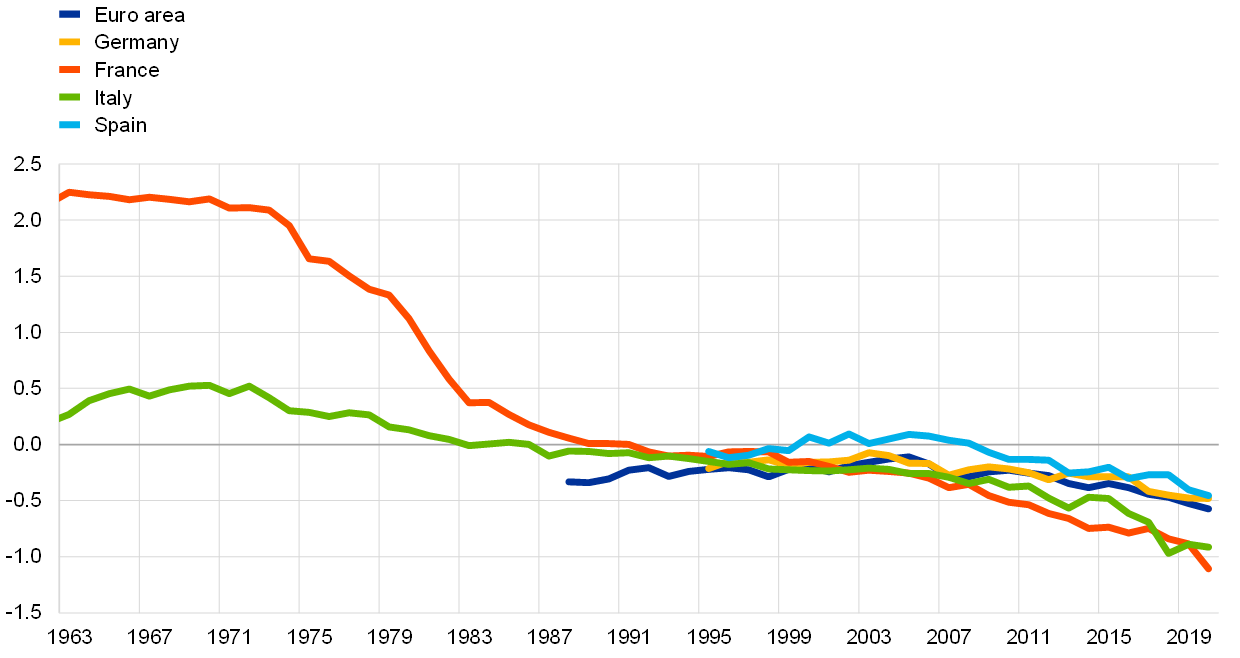

Chart B

Net imports of fossil fuel products

(kilograms per €1,000 of GDP – expressed as a logarithm)

Sources: Eurostat, Insee, Istat and ECB calculations.

Note: The chart shows net imports of coal, coke, briquettes, petroleum, petroleum products and related materials, and gas, natural and manufactured, relative to GDP (kilograms per €1,000 of GDP in 2010 prices).

Given the current oil price increase, the loss in the level of euro area potential output in the medium term can be estimated at around 0.8%. According to elasticities derived from the macroeconomic models used to produce the Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, an increase of 1% in oil prices would imply a decline in the level of euro area potential output of around -0.02% in the medium term. Assuming a permanent oil price shock of 40% – equivalent to the deviation of the oil price assumption used in the June 2022 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections compared with the average for the period 2017-20 – the level of potential output in the euro area would be revised down by -0.8% after four years (Chart C). This constitutes a somewhat limited shock, which should be seen in the context of the cumulative increase in potential output, estimated by the European Commission to hover at around 5.2% for the next four years. Furthermore, this assessment appears to be consistent with other estimates, as previous work by the ECB suggests an elasticity of -0.02 for the long-term elasticity of GDP to oil prices globally, implying a similar effect of the current oil price shock on the long-term level of GDP.[8]

Chart C

Distribution of the impact of the recent increase in oil prices on the level of potential output across euro area countries

(percentage deviations)

Source: ECB calculations based on elasticities derived from the macroeconomic models used to produce the Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area.

Notes: The scenario is based on the June 2022 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, in deviation from a counterfactual where the price of oil is fixed at the average for the period from the fourth quarter of 2017 to the first quarter of 2019. Around the euro area average, shaded areas denote the deciles of the impact of the current oil price shock on the level of potential output after four years, by country, for the nineteen euro area countries.

However, considerable uncertainty surrounds this analysis, notably in relation to the persistence of the shock and to policy responses. On the one hand, the magnitude of the shock is based on futures prices for the period 2022 to 2024, which can be very volatile. As a result, the estimates for the scale of the loss of potential output can change significantly. On the other hand, the monetary policy response to the inflationary pressure from an oil price increase can partially mitigate its persistence and reduce the medium-term effect on potential output by stabilising the macroeconomic cycle and firmly anchoring inflation expectations, thus limiting hysteresis effects. In addition, current technological and economic conditions differ considerably from those prevailing during earlier oil price shocks. This situation may mean that production technology can adjust more quickly to the change in input prices. In particular, for transportation and household energy consumption, viable green alternatives exist that are far less dependent on oil.[9]

See the Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2022.

The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil rose by 168% in 1974, followed by a rise of 51% in 1979 and 67% in 1980. The shocks were triggered by political events affecting the main oil-producing countries. For additional comparisons, see “Today’s oil shock pales in comparison with those of yesteryear”, The Economist, 15 March 2022.

Demand factors linked to the recovery of the global economy after the pandemic have also played a role in the recent increase in oil prices. For a breakdown of oil prices into demand and supply factors, see “Energy price developments in and out of the COVID-19 pandemic – from commodity prices to consumer prices”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2022.

Temporary oil price changes are not expected to affect potential output, but mainly the business cycle. However, an environment of volatile oil prices – although not resulting in higher prices on average – may also have an impact on investment decisions and as a result on potential output. See Estrada, A. and Hernández de Cos, P., “Oil prices and their impact on potential output”, Occasional Paper, No 0902, Banco de España, 2009.

On the one hand, see the box entitled “The scarring effects of past crises on the global economy”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2020. On the other hand, see, for instance, Darby, M. R., "The Importance of Oil Price Changes in the 1970s World Inflation", NBER Chapters in The International Transmission of Inflation, 1983, pp. 232-272; and Kilian, L., “The Economic Effects of Energy Price Shocks”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 46(4), 2008, pp. 871-909.

Blanchard, O. J. and Galí, J., “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why are the 2000s so Different from the 1970s?”, Working Paper, MIT Department of Economics, No 07-21, 2008.

Rühl, C. and Erker, T., “Oil Intensity: The curious relationship between oil and GDP”, M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series, No 164, Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard University, 2021.

Schnabel, I., “Reflation, not stagflation”, opening remarks at a virtual event organised by Goldman Sachs, Frankfurt am Main, 17 November 2021.

The rise in the oil price has coincided with a sharp rise in the price of natural gas, and this may amplify the negative effects of oil prices on activity and potential output by de facto significantly reducing the possibilities for substituting the use of oil with gas.